Treating liver cancer

Treatment for liver cancer depends on several factors, including the stage and location of your cancer, your overall health, the condition of your liver, and your preferences. Surgery is often used to treat liver cancer. Other options include tumour ablation, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

The order and type of treatment you receive depend on your individual situation. You might have one or more of these treatment options. You may have chemotherapy or radiation therapy before or after surgery, or you might not have surgery at all.

This section provides information about the different treatment options available, your treatment team, how to make treatment decisions, and what to expect during and after treatment.

Treatment options for liver cancer

Treatment goals

Treatment for liver cancer depends on several factors, including the stage of your cancer, where it's located, your overall health, and your preferences.

When discussing treatment, your doctor will explain what the treatment aims to achieve. Understanding this intent helps you make informed decisions about your care.

Treatment for liver cancer generally has one of three goals:

1. To cure the cancer

Some treatments aim to remove all the cancer and cure the disease. This often involves surgery, sometimes combined with other treatments. Curative treatment works best when the cancer is found early and hasn't spread to other parts of the body.

2. To control cancer growth and help you live longer

If the cancer cannot be completely removed, treatment can still slow its growth, ease symptoms and help you live well for longer. This is sometimes called anti-cancer therapy and may include chemotherapy, tumour ablation or radiation therapy.

3. To manage symptoms and improve comfort

When the cancer has progressed, the focus may shift to helping you feel as well as you can. This is called symptom palliation or supportive care. It might involve pain relief, help with nutrition, and emotional or practical support. Supportive care can be given on its own or alongside cancer treatment.

In many cases, the severity of co-existing liver disease affects the treatment options and needs to be treated appropriately.

Supportive (palliative) care can be given on its own or alongside cancer treatment.

Common treatments

Common treatments for liver cancer include surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. You may need to have just one of these or a combination of treatments, depending on your diagnosis.

Your treatment team will explain what's recommended for you.

- Surgery is often the main treatment for early-stage liver cancer (cancer that has not spread toother organs).

- Tumour ablation aims to destroy liver cancer without the need to remove it. You may have tumour ablation if your tumours are less than 3 cm across and you can’t have surgery, or are waiting for a liver transplant.

- Chemotherapy uses special medicines to kill cancer cells. It may be offered to patients with liver cancer.

- Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses strong X-ray beams to damage cancer cells. It may be used when tumours can’t be treated with surgery or chemotherapy. Radiation therapy can also be used to try to shrink the tumour before surgery, to increase the chance of successful surgical removal.

- Clinical trials test new treatments to see if they work better than current ones. Joining a trial can give you access to new medicines and extra care from your health team.

Emerging treatment options

Targeted therapies are drugs that target specific genes and proteins involved in cancer growth. Immunotherapies are one type of targeted therapy.

Targeted therapies are only effective for some cancers, so you may need to undergo pathology testing to see if they will benefit you.

Immunotherapy has been shown to work well with chemotherapy for certain types of liver cancer. Immunotherapies are usually delivered as a single injection or infusion per session, and often there are several sessions.

Immunotherapies and other targeted therapies are rapidly evolving, with the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approving new therapies all the time. The costs of these therapies are also changing, as some get listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

Your doctor will let you know which therapies are available at the time of your treatment, and which might suit you.

Getting ready for treatment (prehabilitation)

Getting ready for treatment means helping your body and mind be as strong as possible before you start. It’s like training for a big event. The better prepared you are, the better you’ll cope.

People who prepare often recover faster, have fewer problems after treatment, and feel better overall.

Here are some ways to get ready:

- Move your body: Try to be active in ways that feel safe for you. Even short walks each day can help. An exercise expert (called an exercise physiologist) can make a plan that suits your fitness level.

- Eat well: A dietitian can help you make sure your body has the energy and nutrients it needs. You might need smaller meals more often or use supplements if eating is hard.

- Healthy habits: If you smoke, try to quit. Cutting down on alcohol also helps your body heal and makes treatment easier.

- Look after your mind: It’s normal to feel worried or scared. Talking to a counsellor, practising mindfulness, or learning ways to relax can help you feel calmer.

Your healthcare team can connect you with people who can help with each part of your plan. The most important thing is to start as soon as you can after being diagnosed.

Your treatment team

Liver cancer requires expertise from multiple specialists working together. You'll be cared for by a multidisciplinary team of professionals from different fields who meet regularly to discuss your case and coordinate your care.

Your main doctor

One doctor takes responsibility for coordinating your treatment. Depending on your situation, this might be:

- a surgeon (if surgery is planned)

- a medical oncologist (if chemotherapy is your main treatment)

- a hepatologist (liver specialist)

- a gastroenterologist (specialist in the digestive system).

This doctor acts as your main point of contact and ensures all aspects of your care work together smoothly.

The multidisciplinary team

The rest of your multidisciplinary team will be made up of a mix of medical specialists, allied health professionals and supportive care professionals.

Each team member brings special skills to make sure all parts of your care are looked after. They meet regularly to talk about your case and agree on the best treatment approach.

The make-up of this multidisciplinary team may change at different stages of your treatment, but may include:

| Medical specialists | Allied health professionals | Supportive care professionals |

|

|

|

Once you have had all your tests and investigations, your multidisciplinary team will meet to discuss the results. The multidisciplinary team will use their expert knowledge to review your case and agree on the best treatment options for you.

Rural and regional hospitals are often part of a network linked to metropolitan specialist centres. This ensures that the best treatment and care are available to all patients, regardless of where they live in Australia.

Making treatment decisions

Making choices about your treatment is an important part of your cancer journey. You have the right to be involved in every decision about your care. Your healthcare team is there to help you understand your options and support you to make choices that feel right for you.

Getting the information you need

To make an informed decision, it helps to know as much as you can about your treatment choices. Your treatment team will explain:

- the different treatment options available to you

- the goals of each treatment (for example, cure, control, or symptom relief)

- the benefits and risks of each option

- possible side effects and how they might affect you

- what treatment involves, including how long it takes, where it happens, and how often

- how it might affect your daily life.

Things to think about

Everyone’s situation is different. When making treatment decisions, you might want to think about:

- your personal goals and what matters most to you

- your overall health and how fit you feel

- the side effects and how they could affect your quality of life

- practical issues such as travel, time off work, or caring for family

- your own values, beliefs and preferences.

Questions to ask

It can help to write down your questions before appointments. You might like to ask:

- Based on my specific cancer, what treatment gives me the best chance of long-term survival?

- If surgery is recommended, how much of my liver will be removed? How will this affect eating and digestion?

- What's the typical recovery time for each treatment option?

- How will treatment impact my ability to work, care for family, or maintain other responsibilities?

- What happens if I don't have treatment, or if I delay treatment?

- Are there clinical trials I should consider?

- What supportive care is available to manage side effects?

- Can I get a second opinion?

- What are the costs involved, and what financial assistance is available?

Taking your time

While liver cancer requires prompt attention, you typically have time to:

- absorb information and ask follow-up questions

- discuss options with family or trusted friends

- seek a second opinion if desired

- research and reflect on what feels right for you

Your team will indicate if any decision needs urgency. Otherwise, taking days or even a couple of weeks to consider major treatment decisions is reasonable and expected.

Surgery for liver cancer

Surgery offers the best chance of curing liver cancer. Only a small number of cases are suited to surgery.

Is surgery an option for me?

Surgery may be an option if you have been diagnosed with a liver cancer that has not spread to other organs and is not significantly attached to major blood vessels.

Your doctor may call your cancer operable or resectable. If the tumour partly surrounds some major blood vessels, it may be referred to as borderline operable.

You may be offered surgery in these cases, depending on the vessels involved, but it is more likely that you will be offered preoperative treatment, such as chemotherapy, before surgery is considered.

Types of surgery

Liver resection (hepatectomy)

Surgery that removes part of your liver is called a liver resection or hepatectomy. The amount of liver that is removed depends on the size and location of the cancer.

A resection may benefit patients with compensated liver disease. The liver can regenerate (grow back to its original size) and work normally after a resection. Sometimes, the gallbladder and part of the diaphragm will also be removed.

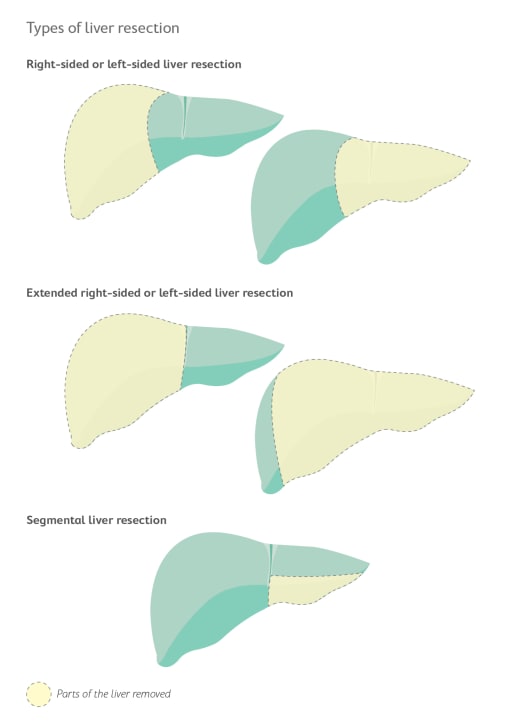

There are three types of liver resection, based on how much of the liver is removed:

- Right-sided or left-sided liver resection is when the right or left part of the liver is removed.

- Extended right-sided or left-sided liver resection is when most of the liver is removed.

- Segmental liver resection is when a small section of the liver is removed.

A hepatectomy is a complex surgery, and you may need to stay in hospital for 5 to 10 days. The liver usually grows back to its normal size within a few months. During this time, you may experience jaundice, but this should disappear as your liver grows back.

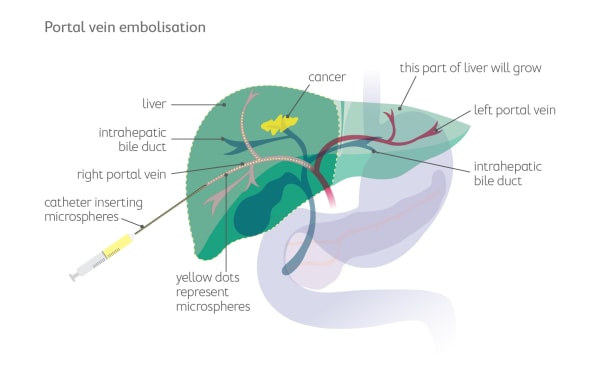

Portal vein embolisation (PVE)

Before major liver surgery, the surgeon may suggest you have a procedure called portal vein embolisation (PVE).

PVE means blocking off part of the blood flow to the area of the liver that has liver cancer. This is done by injecting microspheres into a portal vein (the main blood vessels in the liver). PVE increases the size of the healthy part of the liver by allowing it to grow. This is done about a month before you have surgery to remove the cancer.

Liver transplant

If your tumour has not spread to other parts of your body but your liver is damaged, you may be offered a liver transplant. This is when the whole liver is removed and replaced with a healthy liver from another person (called a donor).

A liver transplant may benefit patients who also have cirrhosis, including those with decompensation, and for patients with a tumour volume within accepted international guidelines.

To be considered for a liver transplant, you must:

- be reasonably fit

- not smoke or take illegal drugs

- have stopped drinking alcohol for at least 6 months.

Donor livers are rare, and it may be many months before a suitable liver is available. You may have tumour ablation or TACE to control the cancer while you wait for a donor.

A liver transplant is a complex surgery. You may need to stay in hospital for up to 3 weeks, and it may take 3 to 6 months to fully recover.

Your treatment team will watch you closely for signs that your body is rejecting the new liver or that the tumour has returned. You will need to take medications called immunosuppressants for the rest of your life to stop your body from rejecting the new liver.

When the cancer can’t be removed with surgery

If the cancer can’t be removed with surgery, you may have some other surgical procedures to reduce your symptoms.

Stent placement

Sometimes, the cancer can cause a blockage in your bile duct. If this happens, you might need a stent to be placed.

A stent won’t treat the cancer, but it will help to relieve the blockage caused by the cancer so that you are more comfortable.

A bile duct stent is a small tube that sits in the bile duct. It helps keep your bile duct open so that bile can pass through the bile duct to the duodenum.

The two ways a stent can be inserted are:

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, where an endoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a camera on the end) is used to see the blockage and place the stent

- percutaneous stent placement, where the stent is placed through the skin of the abdomen using a long, thin needle, and an ultrasound or X-ray is used to guide the needle.

Paracentesis

If you have ascites (a swollen abdomen caused by a build-up of fluid), you may need to have a procedure called paracentesis, or an ascitic tap.

Paracentesis won’t treat the cancer, but it will help to relieve pressure in the abdomen caused by the cancer so that you are more comfortable.

Your doctor will insert a plastic tube into your abdomen that is connected to a drainage bag outside the body. When all the fluid has drained, the tube is removed. You may be prescribed medications called diuretics to slow down the build-up of fluid.

What to expect when having surgery

Before surgery

- You’ll have several tests to check you’re ready for the operation.

- You’ll meet your surgical team to talk about the benefits, risks and what recovery will look like.

- You might start prehabilitation to improve your fitness and nutritional state.

During your hospital stay

- Most people stay in hospital for 5–10 days after surgery for liver cancer.

- You may start your recovery in an intensive care or high-dependency unit.

- Your team will help manage pain and watch for any problems.

Recovery at home

- Healing after liver surgery takes time and patience. You’ll need to give your body a chance to rest and get stronger.

- It may take 6 to 12 months for you to fully recover from the procedure. Try to move a little more each day but listen to your body. You’ll have some good days and some harder ones.

Getting support

Recovery from liver surgery isn't something to navigate alone. Lean on:

- your surgical team for medical concerns

- a specialist dietitian for nutritional guidance

- family and friends for practical help and companionship

- Pancare's Support service to connect with others who've had similar surgeries.

Remember, recovery takes time. Most people gradually find their new normal, though it may look different from life before surgery.

Tumour ablation for liver cancer

If your tumour is less than 3 cm across and you can't have surgery or are waiting for a liver transplant, you may have a tumour ablation. Ablation destroys the tumour without removing it. The most common type of ablation is thermal ablation.

Types of ablation

There are several types of thermal ablation:

- radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses high-energy radio waves to heat and destroy cancer cells

- microwave ablation (MWA) uses electromagnetic waves to heat and destroy cancer cells

What to expect

During the procedure, your doctor will use an ultrasound or CT scan to guide a thin needle through your skin and into the tumour. Energy is then passed through the needle to heat and destroy the cancer cells.

You may have a general anaesthetic or sedation during the procedure. You may need to stay in hospital overnight for observation.

Chemotherapy for liver cancer

Chemotherapy uses special medicines to kill cancer cells or stop them from growing.

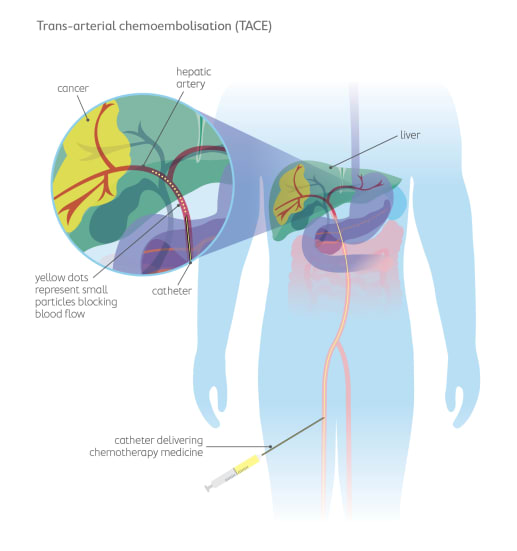

For liver cancer that has not spread, the most common type of chemotherapy is trans-arterial chemoembolisation (TACE). This delivers high doses of chemotherapy straight into the tumour.

Trans-arterial chemoembolisation (TACE)

TACE is a procedure where a catheter (a thin, flexible, hollow tube) is inserted through an artery in your inner thigh to a large artery in your liver. Chemotherapy medicines are injected through the catheter and into the artery. Small particles are then injected into the artery to block the flow of blood for a short time, so the chemotherapy stays in the tumour.

Depending on the type of liver cancer, TACE may be the only treatment used, or it could be given before a liver transplant or major liver resection to control the cancer (known as neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

Common side effects of TACE include:

- Pain

- Fatigue

- Fever and flu-like symptoms

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite

Getting support

Chemotherapy can be physically and emotionally tough. You don’t have to go through it alone.

Your care team, a dietitian, or Pancare's Support service can help you manage side effects, plan meals, and find emotional support.

Radiation therapy for liver cancer

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy X-rays to destroy cancer cells. Modern radiation techniques target the cancer cells precisely, so it is called a localised treatment.

The doctor in charge of your radiation therapy is called a radiation oncologist.

Will I have radiation therapy?

In liver cancer, radiation therapy may be used when tumours can’t be treated with surgery or trans-arterial chemoembolisation (TACE).

Radiation therapy can also be used:

- before surgery, to shrink the tumour and increase the change of successful removal

- after surgery, to kill any cancer cells that are left over after a tumour has been removed

- when cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

How radiation therapy works

Radiation therapy is given by a machine that directs beams of radiation at the cancer from outside your body.

You won’t see or feel the radiation, but it works inside your body to damage the DNA of cancer cells so they can’t keep growing.

What to expect during radiation therapy

Before treatment

- You’ll have a planning session to prepare for radiation therapy.

- You might have a CT scan to help your team map out the exact treatment area.

- Small dots or tattoos may be placed on your skin so the radiation can be aimed accurately each time.

- Your team will explain how many treatments you’ll need and what to expect.

During treatment

- Treatment usually happens once a day, Monday to Friday.

- Each visit lasts about 15–30 minutes, but the radiation itself takes only a few minutes.

- You’ll lie still on a treatment bed while the machine moves around you.

- You won’t feel the radiation, and you’ll be able to go home afterwards.

- Most people have treatment for several weeks.

Side effects and how to manage them

Side effects usually appear slowly during treatment and improve a few weeks after it finishes. Everyone reacts differently, but common effects include:

- feeling tired

- skin redness or irritation in the treated area

- nausea or loss of appetite

- diarrhoea or softer bowel motions

- discomfort or a warm feeling in the abdomen

Your radiation oncology team will help you manage side effects. They can give advice about:

- gentle skin care

- anti-nausea or diarrhoea medicines

- eating well and maintaining energy

- when to contact your doctor if you’re worried.

Getting support

It’s normal to feel tired or emotional during treatment.

Your healthcare team can help with symptom control, nutrition, and emotional wellbeing.

You can also reach out to Pancare's Support for practical advice, counselling, and connections with others living with liver cancer.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new treatments or new ways of using existing ones.

Clinical trials for liver cancer look at different treatment options, with the aim of finding more effective treatments to improve survival and quality of life.

For some people, joining a clinical trial can offer access to promising new treatments and specialised care before these options become widely available.

Why consider a clinical trial

Taking part in a clinical trial can give you the chance to try a new approach that may work better than standard care. You’ll be closely monitored by expert doctors and nurses who specialise in liver cancer.

Even if the treatment being tested doesn’t benefit you directly, your participation helps researchers learn more about the disease and improve care for future patients. Many people find this sense of contributing to progress reassuring and empowering.

What kinds of trials exist

There are many different types of clinical trials.

Some test new chemotherapy drugs or combinations, while others explore targeted therapies that act on specific changes in cancer cells.

Researchers are also studying new ways to use immunotherapy to help the body’s own immune system fight cancer.

Other trials look at surgical techniques, how to better manage symptoms or side effects, or how to detect liver cancer earlier.

Each trial has its own entry requirements, called eligibility criteria. These might include the type and stage of your cancer, your previous treatments, your general health, and sometimes genetic features found in your tumour.

Your healthcare team can explain which kinds of studies are currently running and whether one may be right for you.

Finding clinical trials

If you’d like to explore current liver cancer trials, speak to your oncologist or visit trusted websites such as australiancancertrials.gov.au or the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group.

You can also contact the Pancare Foundation for guidance and information about studies in Australia.

Complementary and alternative therapies

Many people with liver cancer look for ways to feel better and support their wellbeing during treatment.

Complementary and alternative therapies are two types of approaches people sometimes use. It’s important to understand how they differ, and how they can safely fit into your care.

Understanding the difference

- Complementary therapies are used alongside standard medical treatments such as chemotherapy, surgery or radiation therapy. They aim to help you relax, manage symptoms, and improve your quality of life. Examples include meditation, yoga, massage, acupuncture, and relaxation techniques.

- Alternative therapies, on the other hand, are used instead of standard medical treatments. These approaches have not been proven to treat cancer and can sometimes be harmful or interfere with your care.

For this reason, alternative therapies are not recommended as a replacement for evidence-based treatment.

Complementary therapies that may help

Some complementary therapies can be safely used to help with relaxation or symptom relief, as long as your healthcare team agrees.

- For relaxation and wellbeing: Gentle exercise, yoga, meditation, mindfulness, aromatherapy, massage (with your doctor’s approval), music therapy, and art therapy can help reduce stress and improve mood.

- For specific symptoms: Acupuncture and acupressure wristbands may help reduce nausea or pain. Some people find ginger tea or tablets helpful for nausea.

Simple breathing and relaxation exercises can ease anxiety and support sleep.

Dietary supplements

It’s common to wonder whether vitamins, minerals, or herbal products could help.

Some may be safe, but others can interfere with chemotherapy or other cancer treatments.

Always tell your healthcare team about any supplements you’re taking or thinking about taking. They can check for possible interactions and advise what’s safe.

Remember:

- High doses of some vitamins can be harmful.

- ‘Natural’ doesn’t always mean safe.

- Many products make claims that are not supported by science.

If in doubt, ask your doctor, pharmacist or dietitian before starting anything new.

Making informed choices

Before starting any new therapy, take time to check that it’s safe and worthwhile.

Talk to your healthcare team. They need to know everything you’re using. You can also ask:

- Is this safe to use with my cancer treatment?

- What are the possible risks or side effects?

- What evidence supports this therapy?

- How much will it cost and how often would I need it?

Follow-up care

After your initial treatment is complete, you'll enter a phase of follow-up care. This is an important part of your cancer journey.

Follow-up care involves:

- regular check-ups with your healthcare team

- watching for signs of cancer coming back

- managing ongoing side effects

- supporting your recovery and wellbeing

- coordinating care between specialists and your GP.

Your follow-up care plan

Every person’s recovery is different. Your healthcare team will create a personalised follow-up plan that explains:

- who your main contact person is (such as a nurse or specialist)

- how often you’ll need check-ups and who you’ll see

- which tests you may need and how often they’ll be done

- what to expect at each visit

You may have blood tests and CT or MRI scans from time to time to check for any changes.

These tests help your doctors see how you’re healing and detect any possible signs of the cancer returning early.

Managing ongoing issues

Some people continue to experience side effects after treatment, such as fatigue, digestive changes, or problems with appetite.

Your care team will support you to manage these issues and maintain your strength.

What to watch for

Your doctor will tell you about symptoms that may need to be checked quickly.

These might include:

- new or worsening pain in your tummy

- unexpected weight loss or loss of appetite

- persistent vomiting that stops you from eating

- new lumps, swelling or discomfort anywhere in your body.

If you notice any of these symptoms, or anything that worries you, contact your healthcare team or GP as soon as possible.

Looking after yourself

Recovery takes time, both physically and emotionally. Keep communicating with your care team and let them know how you’re feeling.

Gentle physical activity, a balanced diet, rest, and emotional support from friends, family, or a counsellor can all make a big difference.

If you’d like extra support, Pancare’s Support service can connect you with nurses, counsellors, dietitians and others who understand what you’re going through.

Want to talk?

Speak to an upper GI cancer nurse or counsellor, we're here to provide you with the support you need. Support available to anyone impacted by upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancer. Monday to Friday, 9am-5pm.